Spoiling foods, souring wine and worsening wounds have a common culprit — a process called oxidation. Although the ill effects of these chemical reactions can be curtailed by the action of antioxidants, creating a sturdy platform capable of providing prolonged antioxidant activity is an ongoing challenge.

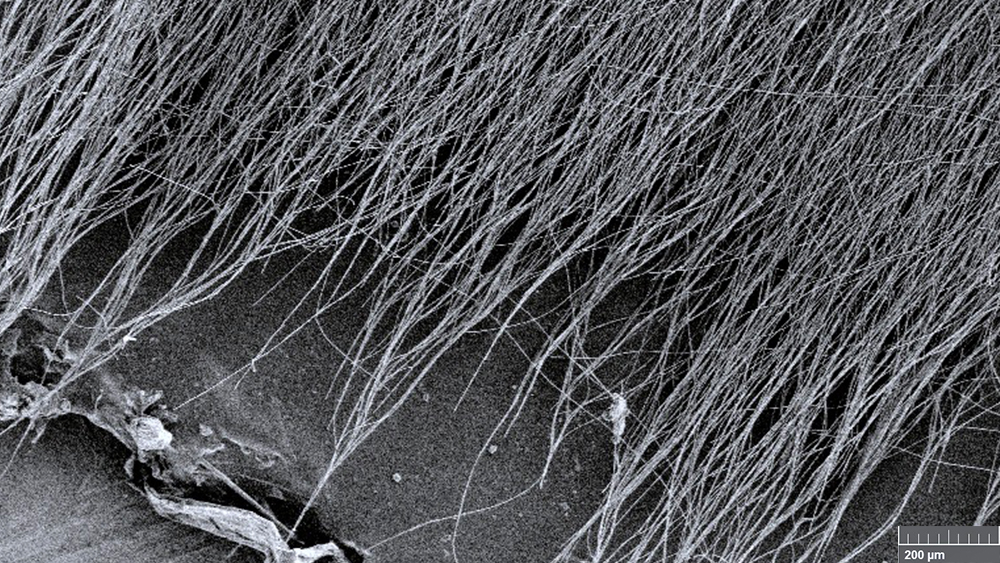

Researchers at Texas A&M University might have solved this problem with their new antioxidant mats. Made from an intertwined network of ultra-fine strands of a polymer and an antioxidant found in red wine, the researchers said these mats are strong, stable and capable of delivering antioxidant activity for prolonged periods of time.

“Our innovation is that we have fine-tuned the steps needed to spin defect-free, ultra-microscopic fibers for making high-performing antioxidant mats,” said Adwait Gaikwad, a graduate student in Dr. Svetlana Sukhishvili’s laboratory in the College of Engineering. “Each fiber is intermolecularly linked to several antioxidant molecules, and so the final mat, which is made of millions and millions of such fibers, has enhanced antioxidant functionality.”

A description of their study is in the February issue of the journal ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

Although oxidation is a common natural phenomenon, left unchecked this chemical reaction can be detrimental. For example, in alcoholic beverages, too much oxidation leads to the formation of acetaldehyde from alcohol, altering the drink’s taste, color and aroma. In the body, oxidative stress causes a buildup of free radicals that can harm healthy cells and body tissue.

However, oxidative reactions can be kept in control by the action of antioxidants. These compounds readily combine with ambient oxygen or donate electrons to neutralize charged radicals. Of the many antioxidants, a molecule found in red wine, called tannic acid, is particularly attractive because it is also antibacterial and antiviral. The researchers said these remarkable properties are due to the presence of groupings of atoms called polyphenols within tannic acid’s molecular structure.

In past studies, antioxidants were blended into synthetic mats made by mixing a polymer and antioxidants together, then flattening them into a sheet. But these mats have lower functionality because the surface area for antioxidant activity is limited.

To increase the surface area for antioxidant activity, the researchers created an antioxidant mesh made with ultrafine fibers of polymer and tannic acid. Thus, each strand of this mesh-like mat could contribute to antioxidant activity.

“We have created antioxidant mats with a high surface area, robust mechanical properties and the ability to provide long-term antioxidant protection,” said Gaikwad. “Also, the release of tannic acid is on-demand — the hydrogen bonds hold the antioxidants in the material until there is an external stimulus, like pH. These properties make our mats suitable for diverse applications, from bandages for wound-healing to inner linings of containers for food storage.”

This work is also supported by the National Science Foundation.