Team gleans new insights on key material

Engineers from Texas A&M University and Virginia Tech report important new insights into nanoporous gold--a material with growing applications in several areas, including energy storage and biomedical devices--all without stepping into a lab.

Instead of conducting any additional experiments, the team used image-analysis software developed in-house to “mine” the existing literature on nanoporous gold (NPG). Specifically, the software analyzed photographs of NPG from some 150 peer-reviewed papers, quickly measuring key features of the material that the researchers then correlated with written descriptions of how the samples were prepared. One of the results? A recipe, of sorts, for how to make NPG with specific characteristics.

“We were able to back out a quantitative law that explains how you can change NPG features by changing the processing times and temperatures,” said Ian McCue, a postdoctoral researcher in the Texas A&M Department of Materials Science and Engineering. McCue is lead author of a paper on the work published online in the April 30 issue of Scientific Reports.

The team also identified a new parameter related to NPG that could be used to better tune the material for specific applications.

“Before our work, engineers knew of one tunable ‘knob’ for NPG. Now we have a second one that could give us even more control over the material’s properties,” said Josh Stuckner, a graduate student at Virginia Tech and co-author of the paper. Stuckner developed the software that allowed the new insights.

Other authors are Dr. Michael J. Demkowicz, associate professor in the materials science and engineering department at Texas A&M, and Dr. Mitsu Murayama, associate professor at Virginia Tech.

Nanoporous gold has been studied for some 15 years, but little is actually known about its physical characteristics and the limits of its tunability for specific applications, the team writes in Scientific Reports.

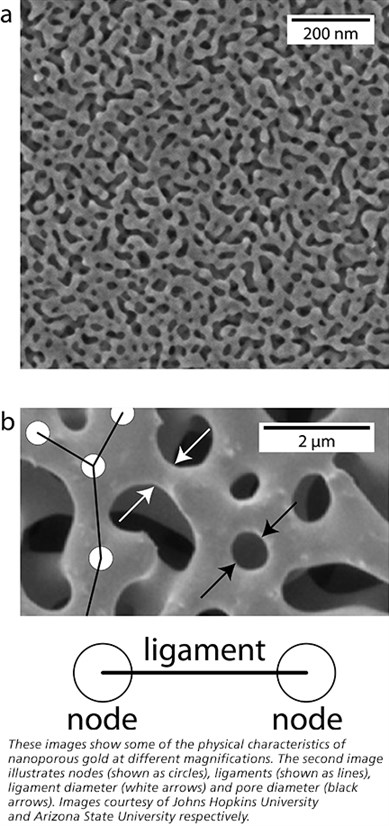

The material is a three-dimensional porous network of interweaving strands, or ligaments. Multiple ligaments, in turn, connect at points called nodes. All of these features are almost unimaginably small. Stuckner notes, for example, that some of the smaller pores would fit about three strands of DNA side by side. As a result, McCue said the overall structure is very complex and it’s been extremely difficult and time-consuming to measure features like the lengths between nodes and the diameters of ligaments. But Stuckner’s software has changed that.

“Manually it might take 20 minutes to over an hour to measure the features associated with one image,” Stuckner said. “We can do it in a minute, or even just tell the computer to measure a whole slew of images while we walk away.”

Earlier attempts to measure NPG features led to very small data sets of five or six data points. The Texas A&M/Virginia Tech team has looked at around 80 data points. That, in turn, allowed the team to create the new quantitative description of NPG features associated with different processing techniques. All that without doing any actual experiments, just clever data-mining and analysis, said McCue.

The work has also led to new publication guidelines for future researchers. Of the 2,000 papers the team originally analyzed, only 150 had useful information.

“We had to throw out a lot of data due to poor image quality or a lack of written information on how a given NPG was processed,” McCue said. “The new guidelines could prevent that, ultimately allowing better data mining not only for NPG but for other materials.”

Their work was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through a program called Designing Materials to Revolutionize and Engineer our Future (DMREF). The DMREF is the NSF’s response to the Materials Genome Initiative, a multi-agency federal program that aims to “discover, manufacture and deploy advanced materials twice as fast, at a fraction of the cost.”

Top picture: By the naked eye, nanoporous gold might look like normal gold, but very small-scale features emerge under high magnification using high-resolution microscopes. Electron micrograph courtesy of Johns Hopkins University.