Despite advances in medical knowledge and treatments, chronic conditions like diabetes and heart disease continue to affect certain people in the United States at higher-than-average levels.

In 2017, the National Science Foundation (NSF) funded an engineering research center (ERC) to address this problem through technology development and outreach. Four universities partnered on the project, and their successes in the last five years have led to a $17.5 million NSF renewal grant to continue the work.

The Precise Advanced Technologies and Health Systems for Underserved Populations (PATHS-UP) ERC is a partnership between Texas A&M University, the University of California at Los Angeles, Rice University and Florida International University. All four schools work with underserved communities in rural and urban areas of their states, with Texas A&M as the lead university.

“People hear underserved in the title and automatically think underrepresented,” said Dr. Gerard Coté, professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Texas A&M and head of the PATHS-UP ERC. “A medically underserved person typically lacks good access to health care. Our underserved also happen to be underrepresented Hispanic, Latinx and African American communities.”

Unequal health issue rates

Over 40% — or two-fifths — of the American population is obese, which leads to heart disease and diabetes, among other chronic ailments. A close look shows underrepresented populations are at a disadvantage. A Black child is over 70% more likely to be obese than a white child. In normal Hispanic communities, a child’s risk falls to about 60% more than a white child. Coté said the heart disease and diabetes numbers in underserved and underrepresented communities are higher and usually compounded by low socioeconomic conditions.

Engineering an increased health care reach

One PATHS-UP goal is to create innovative, robust and affordable technologies engineered to be low-cost, accurate and tough enough for use wherever people live.

For instance, the ERC is developing a rice-grain-sized device to be injected under the skin that tracks and records blood chemistry levels and changes over time. The data is retrieved optically and noninvasively by a watch-like scanner, and the injected device remains in place for future scans.

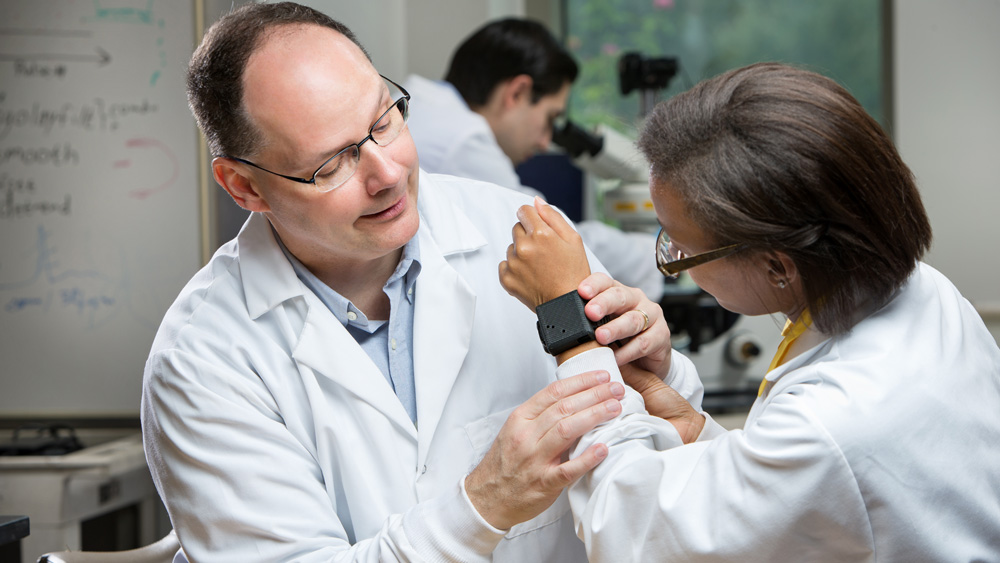

Another device, worn on the wrist, will monitor pulse, body activity and eventually blood pressure without using a cuff. The technology will understand the context — so a high heart rate during a low movement period would trigger an alert — and accurately monitor people of all skin tones and weight ranges.

A third innovation involves paper embedded with nanoparticles 1,000 times smaller than a human hair that will, when combined with a hand-held device, analyze and detect specific biomarkers from a drop of blood. The ambulance crew for a potential heart attack victim facing a 45-minute ride to the hospital can do an immediate blood test on the patient and do another one 30 minutes later during transport. Upon arrival, the hospital will receive two points of data from the patient’s history.

“With data points, plural, we can see trends,” Coté said. “We can see if the biomarkers for a heart attack are going up or down. The current standard of care is to do a blood test when the patient arrives. Doctors get results back from a lab 30 to 45 minutes later and only have one data point to start from.”

Faculty, graduate students, postdoctoral researchers and undergraduate students are all involved in creating and testing the devices. Doctors and other medical care providers, along with over 20 large and small companies, work with PATHS-UP to help get the technology prototyped and taken to the point where the companies can do the final development and manufacturing.

Making medical information part of the culture

The second PATHS-UP goal involves recruiting and educating the diverse precollege, college and postcollege scientists and engineers needed for developing future technology and improving underserved community health.

The ERC achieves this through communicating with and empowering community leaders, students, and teachers; health care providers; and university students and faculty.

Communicating with underserved community participants allows PATHS-UP to share medical information in an approachable way. Empowered teachers create actionable lesson plans on science, technology, engineering, math and health. These plans are shared with their students and other schools. High school students and teachers interested in engineering and health care are recruited to be a part of the research teams in the four universities, where they are mentored by doctoral students doing the research. Many of these doctoral students join cooperative education programs in the communities and learn more about the people they will care for in the future.

In turn, the center learns what’s needed to engineer successful devices from the community. Whether they speak English or Spanish, diabetic patients listening to doctors’ instructions on blood sugar levels might lose track of what to do. PATHS-UP engineers work with engineers and behavioral psychologists to develop apps that use visually clear-cut graphics, like color-coded ranges, and simple if-this-then-that guidelines people can understand.

Future goals

Currently, the universities can only develop technology to a certain point. Beyond that, a company must take over, and that transition can be a challenge. Coté said in the next five years, he would like to explore ways to make that path easier by providing more fully developed and tested technologies.

Coté also said that while many of the ERC technologies would be useful for other diseases, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases are running rampant across the world, even in developing countries — which calls for more community engagement and communication.

“My biggest joy is working with people from so many different areas of expertise who bring different perspectives to the project,” Coté said. “It makes rowing the boat in the same direction a challenge, but it's also one of the greatest rewards.”

The NSF grant will be administered through the Texas A&M Engineering Experiment Station, a state agency that solves problems through applied research and development.